In the post-WWII economic boom, progressivism was on the rise in Halifax. In the 1950s and 1960s, Nova Scotia had achieved a reputation as a leader in race relations and equality among Canadian provinces due to several landmark anti-discrimination laws (Bobier, 4-5). This, combined with the belief that a modernized waterfront would encourage growth for Halifax, led city figures to turn their focus to the Bedford Basin waterfront. Unfortunately, they viewed the historic settlement not as a proud Black community to be supported, but instead as a slum and an obstacle to industrial progress (Bobier, 6-7).

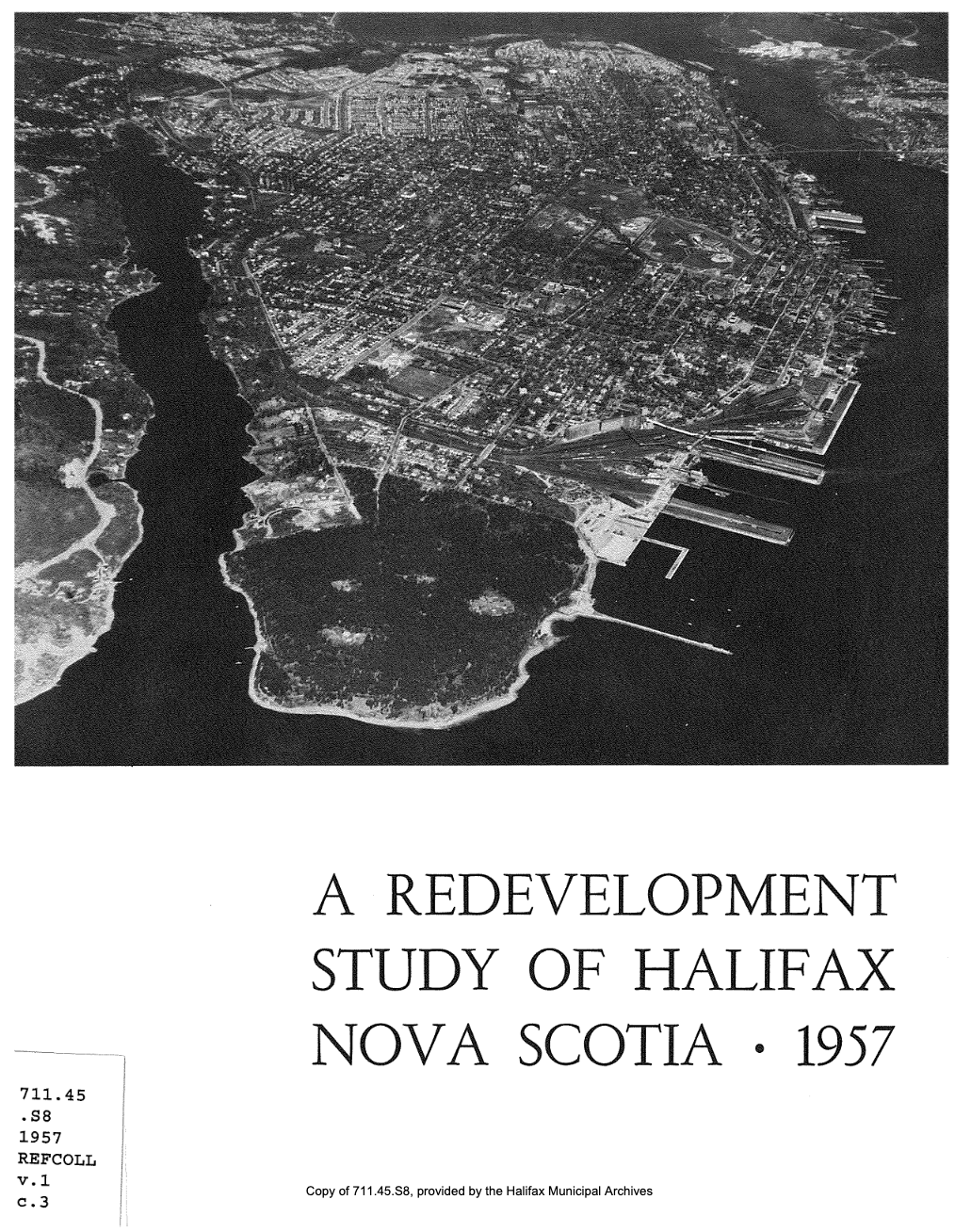

Cover of the Gordon Stephenson report. Note how the cover photo places Africville as far from the foreground as possible.

A report by Dr. Gordon Stephenson laid out a framework for “urban renewal” in Halifax. On the topic of the waterfront, the report labelled Africville as a slum and recommended repurposing the land for “its highest potential use” (Bobier, 7). This report prompted the municipal government to form a Human Rights Advisory Committee to develop recommendations. Although the committee proudly highlighted the three Black caretakers appointed to it, these caretakers admitted to lacking knowledge of Africville. Instead, the process was driven by a white social worker, whose decisions often favoured the city's naive goals of desegregation over the residents’ wishes for more concrete assistance in maintaining their community (Bobier, 12).

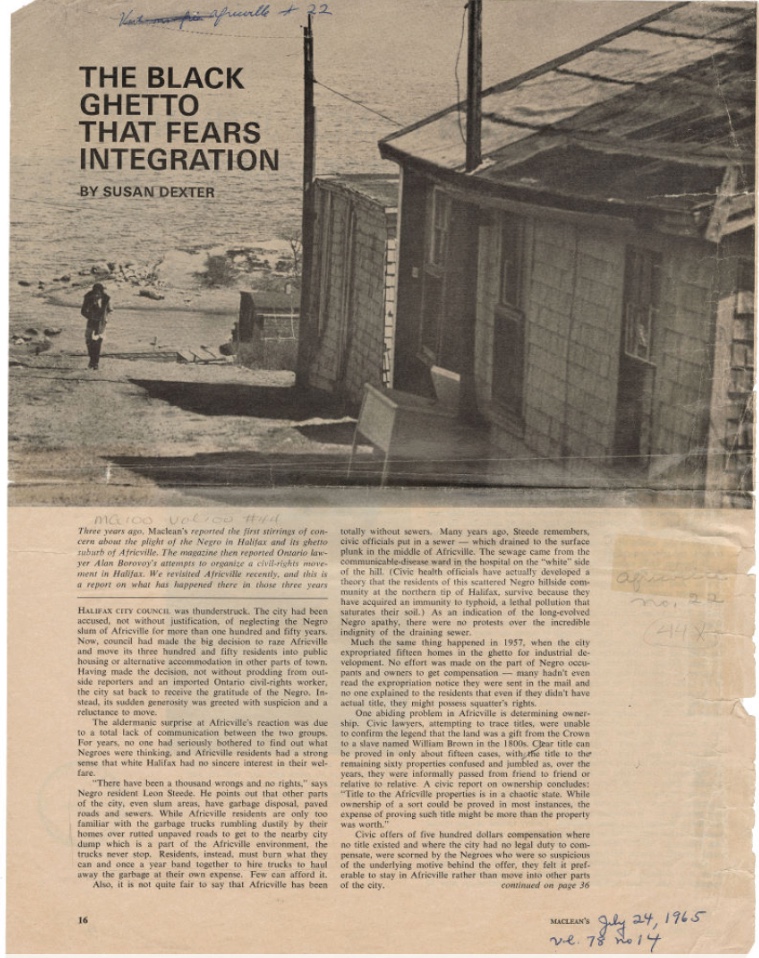

Reports showed that the social worker’s proposed settlements with each property owner varied unfairly based on the negotiating ability of each resident, and it is estimated that fewer than 20% of residents ever spoke directly with the committee (McRae). Despite this, the relocation effort received widespread support from figures in Halifax and abroad, even Time magazine published a piece calling it an effort to "right a historical wrong" (Bobier, 2).

Time magazine article regarding the relocation ("Looking Back, Moving Forward").

The narrative that the land was valuable and needed to be repurposed rang hollow when the city had spent the past half-century ignoring that same land and using it as a dump. Africville, as a settlement, was indeed struggling, but only because decades of neglect had left the infrastructure crippled. This disregard for the residents’ self-determination would culminate in the climax of the city’s siege on Africville: the outright destruction of homes.

“I think we should have a chance to redevelop our own property as well as anybody else … When you own a piece of property, you’re not a second-class citizen. That’s why my people own this land. When your land is being taken away from you and you’re not offered anything, then you become a peasant in any man’s country.

”